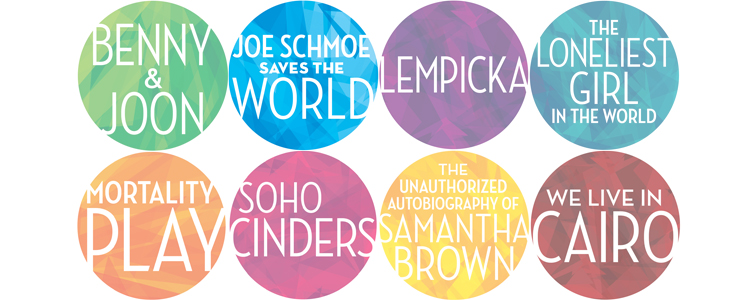

A guest post from Brett Ryback, writer of this year’s show Joe Schmoe Saves the World.

The question of why apply for the NAMT Festival is wrapped up in the larger question of why apply for any festival, or grant or award, etc. It’s certainly no small feat to fill out the application, record the necessary demos, pony up the entry fee, and get it all in the mail on time. Sometimes, even despite the potential production or reading or financial gain, applying for things feels like a burden that gets in the way of the thing you’d rather be doing – writing (or eating, it’s often a toss-up for me). But the actual act of applying comes with its own worthwhile lessons, and I recommend every writer give it a shot once or five times.

- Failure Makes You Stronger

Rejection is part of the business, and learning to handle rejection is one of the best skills an artist can develop. Handling rejection in a healthy way will give you the stamina to keep going through even the toughest slog, AND get better while you do it.

The trick is that you can’t simply disregard rejection, you have to learn from it. Find out why you got rejected, decide whether you agree with that reason, and then adjust your work accordingly. You might learn that your piece is not for every audience, or you might come to understand that a certain quality you thought you were communicating is actually not being received by the reader. Or you might learn that the only way to get ahead is to live in New York City and have famous people sing your songs at 54 Below (Joking!) (Sort of.). Either way – you’re learning how to rebound and move forward. And eventually, that rejection will turn into acceptance.

- Competition Keeps You Current

The temptation to write simply for your own enjoyment is a strong one. And while you may think you have the most universal sense of drama/humor/musical taste, etc., it’s a good idea to take your head out of the sand from time to time and see what other people are responding to. Because let’s face it – writing works of theatre (let alone musical theatre) takes a very long time. Why spend it on show that’s going to be very difficult for anyone else to get behind?

This isn’t to say that you should only write watered-down knock-offs of other shows, or even that you should necessarily cater your ideas to the types of people who select pieces for festivals. But it will help you keep a good gauge of where your work fits in a grander scheme of what is being “well-received.” Perhaps you’re filling a gap, perhaps you’re providing a fresh look on a common theme, or perhaps you’re writing something nobody finds particularly dramatic and well, see lesson #1 above. The point is that having to compete can help you write with a little more intention and a little more edge.

- 150 Words Or Less Is the New Black

Talking about your work is one of the hardest things a writer has to do. It’s like being asked to describe the back of your head. I mean you sure you have a sense of what it looks like – but wouldn’t it just be easier for someone to tell you?

Applying for various festivals and awards will inevitably require you not only to talk about your work, but also to do it succinctly. This will be VERY hard to do. But over time, the better you get, this will be one of the best gifts you will receive from the application process.

Often an application will ask for a short description of your piece – a “logline” in movie parlance, or a “blurb” in newspaper speak. You might think there’s no way to distill your masterwork down to a couple sentences. But aha! There likely is a way. And if you can find it, they will be the most compact, emotion-filled sentences about your characters and your story that you’ve ever uttered. And now you have a surefire way to quickly interest people in your musical.

Distilling your piece down to a couple sentences will not only help you be better able to communicate your ideas to other people, but it will help you learn exactly what your story is (or should be) about. You’ll be able to see immediately what’s working and/or what isn’t. A great way to practice this skill is to create your logline and then verbally share it with friends and family (or your Starbucks barista and the rando on the subway!) Tweak words, add or delete phrases, try different angles. See what gets that prized of all responses: when the listener’s eyes go wide and she can’t help but say, “Oh wow!”

Similarly, this skill will also show you where your ideas may be lacking. For example, let’s say you have to write a synopsis of your show for a grant application. As you write, you may see you’ve got a really strong opening, but then half way through your synopsis the character isn’t really being very active. There’s a lot of talking and being, but not really a lot of doing to move your story forward. That could be an issue in your story. If you find a way to solve it in the synopsis, then you can go and solve it in the actual script.

- The Work Never Ends

The most important lesson of all – and one that you’ll learn whether or not you are able to procure the festivals, grants, or awards you seek – is that the work is the most important thing, and it never ends. Even if you are accepted into a festival of great renown, you will still be responsible for making your project the best it can possibly be. It doesn’t just stop because you’ve gotten past the gatekeepers.

You will always be the best shepherd for your piece. Failing teaches you this constantly. But even when you succeed, it’s an important thing to remember.

The point is, in the application process, it’s easy to believe that simply being accepted is the end goal. But really getting in is only the beginning. It requires constant tenacity, a clear sense of vision and purpose, and a willingness to speak up for yourself and your piece.

And if you want to know the best way to learn how to do that – see lesson #1.