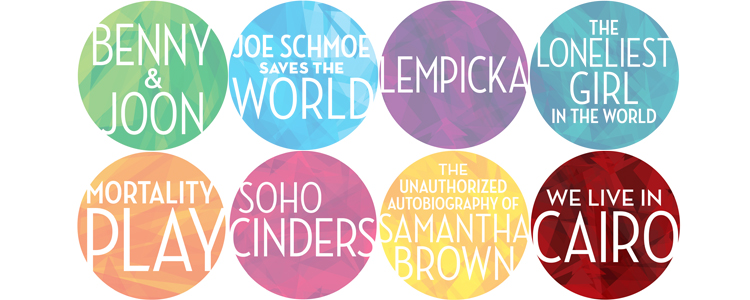

A conversation with Daniel and Patrick Lazour, the writers of this year’s Festival show We Live in Cairo.

Patrick: So Daniel.

Daniel: Patty O.

P: You being the composer in this arrangement, tell us what orchestration does.

D: Well, it takes the score the extra mile, I think. You listen to a Rodgers and Hammerstein score played on piano and it’s just a totally different thing from the, ya know, 70 piece orchestra.

P: And that’s how it was intended.

D: Back in the day.

P: Because they had the money.

D: But it’s funny.

P: It’s all about money.

D: You’re right. But not quite. Because the resourcefulness you have to have now, leads to some pretty interesting things.

P: What’s a good example of that? Because what comes to mind for me is Urinetown.

D: Urinetown! That’s such a great point. Super resourceful. And really, sort of bizarre instrumentation. Bizarre in the best sense, in that it gives this sort of dystopian sound. The reed and the brass give it this neo-baroque feel.

P: Neo-baroque. Definitely. Even this archaic…

D: Ancient! Or something…. But what about you? What are your favorite orchestrations?

P: I would say Sunday in the Park with George.

D: Kills it.

P: Because of its specificity to the time. I think that is also getting to what we talk about with our show—the way that Michael Starobin homed in on period and the artistic sensibility of Georges Seurat.

D: I think of that French horn interval. Bahm-bah. And you’re so right. It’s so 19th century. So Belle Époque.

P: Right. And Georges Seurat. Not to intellectualize this conversation, but he had manifestos. He was a writer just as much as he was a painter. So finding ways to orchestrate those thoughts to create a soundscape is what transports me.

D: Sunday. So great. And rather remarkably, we had the opportunity to work with Michael Starobin…

P: At the O’Neill on We Live in Cairo.

D: He’s just a master. He’s a master of what works and what doesn’t work. He taught us the orchestrator’s job. That is, to take sketches from the composer and fill them in. Talk about painting. It’s a matter of shading and adding detail and “completing the thought.” He said that. He totally understood that We Live in Cairo is a groove-based show. He and I also talked a lot with our Oud player Hadi Eldebek, for example, about how he should really use what he knows about his instrument and culture and filter that into the show. To authenticate it.

P: And this brings up a good point. How much is orchestration a collaborative process?

D: I think it depends. In the olden days, it was much more of a pass-off situation.

P: But that’s old world. That’s ancien regime. What’s nouveau?

D: I think today is much more collaborative, in that musical theatre is sounding more like bands that we listen to. And bands inherently are a team effort. So I think it’s the idea of getting musicians in the room, like Hadi, our incredible percussionist Jeremy Smith, and Eli Zoller our music director. Jeremy for instance heard this score in its super nascent stages and had ideas to contribute even before things were fleshed out on my end. It’s about how our different interpretations can come together.

P: It’s also worth mentioning that with We Live in Cairo, from the first weeks of writing, the idea of orchestration was in our conversation. Am I right?

D: Absolutely.

P: And that, I think is a little bit of an anomaly. There are different ways of going about a show, but usually orchestration comes close to last. But because this show was based in Egypt, we wanted the score to reflect traditional and contemporary Arabic music. Oud, Percussion. And then we needed to figure out how to contextualize these sounds in a musical theatre idiom. And that was all orchestration. What that meant was that we had to start making relationships with musicians who knew this world—and that meant connecting with the Arab community in New York. Fellow Lebanese and, of course, Egyptians.

D: And at NAMT, we’re so thankful to have the opportunity to continue to work with the band.

P: I think, just to wrap up, orchestration is knowing your score in and out, and going from there.

D: And we always try to remember that another instrument’s interpretation of a melody, bass line, accompaniment figure, can be more “right” than the instrument you wrote it on. And that’s the magic of orchestration, really.